Linear Patterns

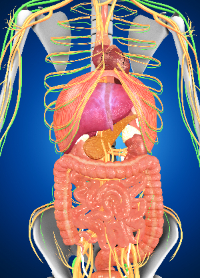

Many things in life and in our bodies follow a linear pattern. Linear patterns adhere to a logical step-by-step progression. To illustrate, think about digestion: this is a great example of a linear process in the body. Food goes into the mouth, and then a cascade of pre-determined processes follows as the food flows through the digestive system, ending with waste products being expelled out the other end (Moseley and Butler, 2017).

Although I didn’t realize it before, when a client tells me their pain suddenly appeared or didn’t have a triggering event, they are attributing a linear pattern to their pain. The model they have adopted is that pain is the consequence of something they did. Hence, an example might be that when the client lifted groceries out of the trunk of their car, they experienced pain in their back. In a linear fashion, one thing follows the other. In this example, it seems like lifting the bag of groceries was the triggering event that resulted in the back pain. The client believes they have caused the pain through this single action. But, as I have recently learned, pain doesn’t work this way. To understand pain, we need to understand emergent patterns. Read on!

Many things in life and in our bodies follow a linear pattern. Linear patterns adhere to a logical step-by-step progression. To illustrate, think about digestion: this is a great example of a linear process in the body. Food goes into the mouth, and then a cascade of pre-determined processes follows as the food flows through the digestive system, ending with waste products being expelled out the other end (Moseley and Butler, 2017).

Although I didn’t realize it before, when a client tells me their pain suddenly appeared or didn’t have a triggering event, they are attributing a linear pattern to their pain. The model they have adopted is that pain is the consequence of something they did. Hence, an example might be that when the client lifted groceries out of the trunk of their car, they experienced pain in their back. In a linear fashion, one thing follows the other. In this example, it seems like lifting the bag of groceries was the triggering event that resulted in the back pain. The client believes they have caused the pain through this single action. But, as I have recently learned, pain doesn’t work this way. To understand pain, we need to understand emergent patterns. Read on!

Emergent Patterns

Emergent patterns can happen spontaneously when many items converge. Sound like the definition of a perfect storm? Likewise, they can dissipate as mysteriously. Yahoo! This means pain can disappear as quickly as it appears. Consider a traffic jam. All the drivers are going along, minding their own business, traveling from here to there. Suddenly and surprisingly, all of these independently moving cars come together at the same location, causing a traffic jam (Moseley and Butler, 2017). Darn, now I’m going to be late! Then, without warning, all of the cars start moving, traffic flows easily, and you relax as you realize you’re going to be on time for your appointment. Emergent patterns depend on many items coalescing at the same time. This is how chronic pain works!

Let’s consider what items may be converging to create pain in our lifting example above. Pain science teaches us that there are external and internal inputs to the pain experience (Gifford, 1998). External inputs come from our body tissues and environment, while internal inputs are stored in the brain and include beliefs, past experiences, knowledge, culture, and more. Adding all of the inputs (emergent items) into the lifting example gives us a broader picture of the event. These include such things as a cold environment, rushing because you are late, tired from a poor night of sleep, a previous experience of pain while doing the same activity, tight back muscles, feeling angry and disappointed because you have overscheduled yourself again, distracted attention, and the beliefs that your back is weak and that lifting is dangerous.

Consider a traffic jam. All the drivers are going along, minding their own business, traveling from here to there. Suddenly and surprisingly, all of these independently moving cars come together at the same location, causing a traffic jam (Moseley and Butler, 2017). Darn, now I’m going to be late! Then, without warning, all of the cars start moving, traffic flows easily, and you relax as you realize you’re going to be on time for your appointment. Emergent patterns depend on many items coalescing at the same time. This is how chronic pain works!

Let’s consider what items may be converging to create pain in our lifting example above. Pain science teaches us that there are external and internal inputs to the pain experience (Gifford, 1998). External inputs come from our body tissues and environment, while internal inputs are stored in the brain and include beliefs, past experiences, knowledge, culture, and more. Adding all of the inputs (emergent items) into the lifting example gives us a broader picture of the event. These include such things as a cold environment, rushing because you are late, tired from a poor night of sleep, a previous experience of pain while doing the same activity, tight back muscles, feeling angry and disappointed because you have overscheduled yourself again, distracted attention, and the beliefs that your back is weak and that lifting is dangerous.

|

Conclusion

Despite knowing that many items contribute to the pain experience and even being told by clients that they notice an increase in pain with stress, lack of sleep, and dehydration, I didn’t have a good model to explain the connection. Now I do! And so do you! Moseley and Butler (2017) note that research has found that most people don’t have a good understanding of emergent patterns. Consequently, we default to using linear patterns to explain life and body processes, including chronic pain. Now you can see how this is a mistake. Linear patterns are not appropriate to explain chronic pain. It takes a multitude of items joining together to create persisting pain–which means there are many treatment options available to reduce it. This is exciting news! Get started today by taking a moment NOW to draw your own input arrows toward your pain. Choose one, the easiest one, to change. Then, notice as your pain starts to decrease.Moseley, GL & Butler, DS 2017, Explain Pain Supercharged, Noigroup Publications, Adelaide, Australia. Gifford, L 1998, ‘Pain, the Tissues and the Nervous System: A conceptual model, Physiotherapy, vol. 84, no.1, pp. 27-36.