Please enjoy an excerpt from my book,

Winning the Injury Game, available on

Amazon.

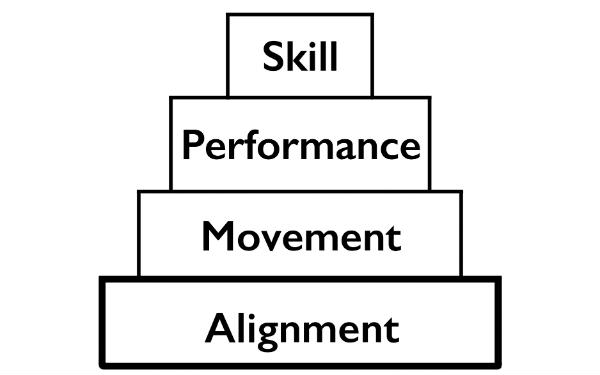

Gray Cook, MSPT, OCS, CSCS, researcher, national lecturer, and author, developed the “Optimum Performance Pyramid” as a model to understand movement. It is a three-tier pyramid; the large base level is labeled “functional movement,” which is topped by “functional performance,” and at the apex, “functional skill.”

1

I like Cook’s model. I agree that all athletes, regardless of sport, should be able to perform functional movements at the base of the pyramid before engaging in more complex activities. However, I am inclined to modify his pyramid and add a bottom layer for physical alignment, which would include proper joint position and muscle biomechanics, as shown in the “Sports Training Pyramid,” shown above.

Cook explains the base of his pyramid, functional movement: “The first level represents the foundation: mobility and stability, or the ability to move through fundamental patterns.”4 In my opinion, mobility and stability, as well as executing proper movement patterns, cannot be successfully attained if the body is out of position and lacks the capability to isolate muscles correctly before coordinating them into patterns, as I discussed in Chapter 8. This is why I’ve added

Alignment to the base of my “Sports Training Pyramid.”

Remember, it is the

position and condition of the body brought into sport that matters. Physical alignment is the infrastructure upon which all other work should be built—weight lifting, aerobic exercise, intervals, plyometrics, etc. The second and third levels of Cook’s pyramid are focused on movement efficiency and specific sports skills, respectively. To attain success in these higher levels, the athlete’s foundation—physical alignment—must be strong. Otherwise, training plateaus and injury may be inevitable.

A client once asked me why, when training for long distance trail running races, his body would consistently begin to fail around 20 miles into his workouts. He just couldn’t pass the 20-mile mark without injury. I explained how he was missing the structural base and biomechanics needed to support longer efforts. He lacked physical alignment; he did not have the proper position and essential muscle engagement patterns necessary to sustain the prolonged running performance he desired. His body could cheat for a while, up to 20 miles, but after that it began to decline. His compensations could only take him so far until his body made him stop. Pain and injury are the body’s way of making us take notice.

Cook, G. (2003).

Athletic Body In Balance: Optimal Movement Skills and Conditioning for Performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.