Our emotional state impacts our chronic pain experience. Thus, feeling safe or threatened can increase, decrease, or completely eliminate the sensation of chronic pain. Essentially, how much something hurts is often dependent on our circumstances and whether we feel secure or in danger. To understand how this works requires knowing the role of pain in the body.

The primary role of pain is protection. And it’s the brain that determines if you are safe or in danger and if you need to be protected or not. The brain does this by analyzing ALL of the inputs it receives. These inputs include physical sensations as well as mental outlook, emotions, and stored information like past experiences, beliefs, and knowledge. The brain considers ALL of this to determine if protection is required. Basically, the brain is asking, Are you under threat? If the answer is yes, it responds with pain because it wants to attract your attention and encourage a change in behavior to keep you safe. (If you need convincing of this idea, please read my blog: Your Brain Interprets Your Pain.)

What is a Threat?

A threat is anything that makes you feel unsafe. Consider the list of items below, some of which are threats and some of which promote feelings of safety. As you read each one, ask yourself this question: Does this make me feel safe or threatened? In other words, when I read this statement, which message is my brain receiving–danger or security?

- Feeling a tight hamstring muscle

- Having an argument with a family member

- Enjoying a favorite meal

- Groaning as you get up from the chair

- Snuggling with your pet

- Expressing gratitude to someone

- Adding weight to your strength exercise

- Ignoring physical hunger cues

- Sitting by a warm fire

- Missing a deadline at work

- Buying yourself a gift

- Referring to your “bad back”

- Telling yourself you won’t heal

- Observing postural misalignments

- Hearing your dog bark at night

- Waking up refreshed after a good sleep

- Walking in nature

- Holding onto a grudge

- Receiving sad news

- Worrying about climate change

- Hearing someone say “I love you”

- Reading a recovery story

- Noticing a pimple on your face

- Watching the waves at the beach

- Tripping on the stairs

- Drinking coffee/tea with a friend

- Reading an engaging book for fun

- Practicing mindfulness

- Looking at your MRI report

- Taking on a new challenge

Although this list could go on and on, I stopped myself at 30 items. The bottom line is this: if you are in danger in any area of your life, the brain interprets it as a threat and may defensively create pain to protect you. As you can see from the list above, threats to safety come in many forms. However, whether or not these threats actually lead to feeling pain depends on two main things: how many threats the brain detects and what your threat baseline level is.

Your Threat Baseline

A threat is a stressor. So, your threat baseline is your stress baseline. Considering the long list of threats above, which is just a sampling, it follows that each of us has a unique combination of safe and threatening items in our lives that result in a different resting level of stress. This is our personal stress or threat baseline. Put another way, each of us has a varied amount of electrical excitement in our nervous system that reflects our stress level. And the position of our baseline affects how quickly and easily we experience chronic pain.

Naturally, the more threats you have, the more stress you have and the higher your baseline. Consequently, the more stress you have, the more likely it is that your brain decides to protect you. In order to do this, it produces the sensation of pain. As an illustration, let’s look at pain in the context of a popular carnival game.

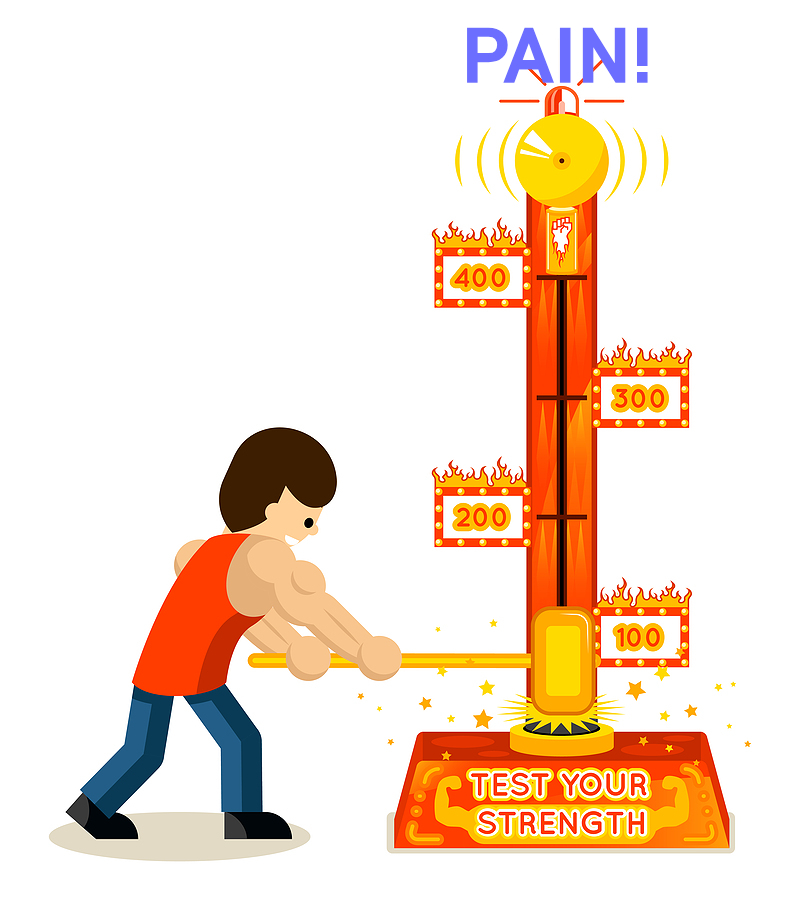

Striking the Pain Bell

At an amusement park, state fair, or carnival, you may have seen and even played the high striker game that measures your strength. As the image shows, the objective is to hit the bottom plate (shown in black) with the hammer as hard as possible to send the striker to the top of the pole and ring the bell. In the image, the striker is the yellow box with a white fist inside that’s hitting the bell at the top of the pole. In our pain bell version of the game, the goal is a bit different from the real game. In our version, we want to keep the striker below the bell.

When using this game as an analogy for pain, the game components represent the following concepts:

- Bell = experiencing pain. When the striker hits the bell, we feel pain.

- Pole = level of electrical excitement in the nervous system, ranging from zero at the bottom to 400 at the top.

- Striker = current position of the threats/stresses.

- Hammer = stimulus that raises the level of excitement in the nervous system. As the hammer hits the plate, the striker rises up the pole, depending on the strength of the hit. Stimuli that could raise the striker include any of the threatening items previously listed. In contrast, safe items on the list can lower the striker.

In the set-up for this game, assume that the resting level of excitement (threat baseline) in the nervous system is when the striker is positioned at the bottom of the pole, just above the black plate, with the numerical value of zero. To avoid pain, the striker needs to stay below 400. The level of the striker rises and lowers on the pole depending on the nature of the inputs. Stressful or threatening inputs move the striker up, while calming or safe inputs move the striker down. Now, let’s look at an example.

Meet Charlie. He has chronic shoulder pain and is going to play our pain bell game.

Upon waking in the morning, he has no pain; his nervous system is at a balanced resting level, and the striker is sitting at the base of the pole. As he is enjoying a warm shower, his phone dings. He’s notified of a meeting he forgot about–a meeting that is scheduled in one hour. This stressful stimulus (threat) is the first hammer strike of the day. With this news, his nervous system’s excitement level increases, and the striker moves up to 100 on the pole.

Charlie dresses and walks to the kitchen. As he boils water for his morning coffee, he realizes he’d forgotten to go to the store on his way home from work the evening before, and he is out of beans. No coffee for Charlie: the second hammer strike of the day. The striker glides up another notch to the 200 marker.

Before leaving home, Charlie takes a moment to pet his cat, lets out a deep sigh, and reassures his feline that everything is going to be okay. This small act comforts his brain and increases his feeling of safety. Now, the striker moves back down to 100.

While driving to the meeting, traffic is stopped. Charlie is going to be late. Hammer strike number three! The striker goes back up to 200. Since Charlie cannot do anything about the traffic, he decides to do some deep breathing to relax while he waits. In response, the striker moves down to 100, away from the pain bell. As traffic starts to move again, Charlie sees the cause of the back-up: an accident with many emergency vehicles. Hammer strike number four. The striker is now hovering at 200, in the middle of the pole.

The final strike happens at the meeting when Charlie is criticized for his work. This is so threatening to Charlie that his nervous system jumps into high alert. The hammer slams down with full force on the plate, the striker zooms to 400 and rings the pain bell–and Charlie’s shoulder starts to ache.

Imagine how this game would change if the threat baseline was at 200. In this case, it wouldn’t take many threatening inputs to ring the bell and feel the pain. Fortunately, many threats are within your control and modifiable. Read more in this blog: Beat Your Pain with the Biopsychosocial Model.

Summary

Pain protects you. Pain often results when the brain decides that you are under threat. A threat is equivalent to a stressor and comes in many forms. Each person has a unique threat/stress baseline. The higher the baseline, the more electrical activity in the nervous system, the quicker and easier pain is produced. However, this baseline can be lowered through calming activities that provide the brain with messages of safety.

Stop scaring your brain to relieve chronic pain!

Moseley, G. L., & Butler, D. S. (2015). The Explain Pain Handbook: Protectometer. Noigroup Publications.