Tennis Elbow, Climber’s Elbow, Golfer’s Elbow—these are all elbow tendonitis injuries. However, despite what you might think, the elbow is often not the problem . . .

What is Epicondylitis?

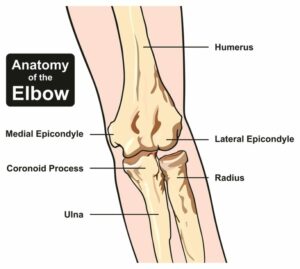

Epicondylitis is simply the technical term for Tennis Elbow, Climber’s Elbow, or Golfer’s Elbow. It comes in two varieties—lateral epicondylitis and medial epicondylitis, depending on which epicondyle is involved.

The Anatomy

Anatomy of the Elbow joint diagram including all bones humerus radius ulna for medical science education[/caption]

Anatomy of the Elbow joint diagram including all bones humerus radius ulna for medical science education[/caption]

You might know that at the elbow joint, on each side of your upper arm bone (humerus), there is a rounded bony structure called an epicondyle. To illustrate, the image to the right shows the lateral (toward the outside of the body), and medial (toward the inside of the body) epicondyles.

Forearm muscles attach to these epicondyles. As the diagram below shows, the muscles on the underside of the arm connect to the medial epicondyle, while the muscles on the top of the arm connect to the lateral epicondyle. The muscles on the underside of the arm turn the hand palm down into pronation, while the muscles on the top of the arm turn the hand palm up into supination.

The muscles of the arm and hand are specifically designed to meet the body’s diverse needs of strength, speed, and precision while completing many complex daily tasks.[/caption]

The muscles of the arm and hand are specifically designed to meet the body’s diverse needs of strength, speed, and precision while completing many complex daily tasks.[/caption]

When playing tennis or other racquet sports—pickleball, racquetball, squash, badminton, and more—the palm supinates to open the racquet to hit the ball. Since these muscles attach to the lateral epicondyle, Tennis Elbow is lateral epicondylitis.

Alternately, while playing golf and while climbing, the arm is in a pronated position, with the palm positioned down to hold the club or toward the rock. Since these muscles are attached to the medial epicondyle, Golfer’s and Climber’s Elbow are medial epicondylitis.

To summarize, Tennis Elbow = Lateral Epicondylitis

Climber’s and Golfer’s Elbow = Medial Epicondylitis

What about the itis?

The epicondyle is where the injury is, but what is the injury? Actually, “itis” means “inflammation.” Therefore, Epicondylitis is inflammation of the forearm tendons in the elbow joint. Tendons are the soft tissues that connect muscles to bones.

Itis injuries are overuse injuries, generally said to be caused by doing too much repetitive movement. For example, if you play too much tennis or golf or climb too long and often, you will have an itis injury. Rest, ice and anti-inflammatory medication are the standard treatment protocols.

Unfortunately, epicondylitis frequently becomes a chronic injury. When this occurs, you are able to play or climb for a while, but then the stress in the elbow joint builds up enough to bring on debilitating pain, which then forces time off from your sport. As a result, to combat the pain, you rest, ice and medicate, but subsequently, the cycle repeats.

In order to heal epicondylitis for good, instead of treating only the symptoms, you must treat the cause of the pain. And it’s important to know this: Epicondylitis can be a symptom of a dysfunction in another part of the body that created a compensated movement pattern. This compensated pattern causes pain at the elbow joint. The next section elaborates!

| Related Blogs: Treat the Cause, Not the Symptom Stretching Your Glutes Isn’t Enough The Most Important Question to Ask About Your Pain |

Uncovering the Cause of Elbow Tendonitis

So, why does your elbow hurt? Is it really because you are doing too much? Perhaps, but maybe not.

In the discussion above, I only mentioned the forearm muscles leading from the hand to the elbow. In the diagram above, you might also notice the muscles leading up from the elbow toward the upper body. These muscles also connect on the condyles. The diagram above is incomplete, though, since it only shows a couple muscles. Additionally, it does not illustrate the connective tissues at all.

To further examine the issue, consider the arm muscles as an interconnected chain. If we do this, we would find–as Tom Myers, fascial expert, did—that the forearm muscles join into the back, shoulders and chest muscles through the connective tissue (fascia). Interestingly, Myers discovered four arm lines that relate to posture and function: “Arm Lines do have a postural function: strain from the elbow affects the mid-back, and shoulder malposition can create significant drag on the ribs, neck, breathing function, and beyond.” (Anatomy Trains)

To further examine the issue, consider the arm muscles as an interconnected chain. If we do this, we would find–as Tom Myers, fascial expert, did—that the forearm muscles join into the back, shoulders and chest muscles through the connective tissue (fascia). Interestingly, Myers discovered four arm lines that relate to posture and function: “Arm Lines do have a postural function: strain from the elbow affects the mid-back, and shoulder malposition can create significant drag on the ribs, neck, breathing function, and beyond.” (Anatomy Trains)

To further elaborate, think about this: The forearm muscles alone do not pronate and supinate the arm. Actually, they work in cooperation with muscles throughout the arm and into the shoulder and back. Another expert, Pete Egoscue, who is the founder of Posture Therapy, notes, “Pronation and supination of the forearms need shoulder involvement. Without the shoulder, most of the function takes place in the elbow and wrists.” (Pain Free)

Like the knee joint, which links the hip and ankle and transfers power and movement between the two, the elbow joint acts as a go-between for the shoulder above and wrist below. So, if the shoulder, the largest joint in the arm line, is rounded (which is actually very common in our society), this impacts the function of the shoulder. Even if the shoulder does not have full range of motion and strength in its designed movements, the body still needs to move. As a result, the small joints of the elbow and/or wrist compensate to get the job done.

As a result of this compensation, the elbow takes on the functions of the shoulder. Now the elbow is doing its job AND picking up the slack for the dysfunctional shoulder. Unfortunately, until the shoulder becomes more aligned and regains its function, the elbow will continue to compensate each time you pick up a racket, hold a golf club, or grip a climbing hold. You can see how this will cause problems!

Exercises to Fix Elbow Tendonitis

In order to regain range of motion and function in your shoulders, practice the following Egoscue Method© exercises. Consequently, these exercises should also alleviate elbow pain.

Standing Shoulder Shrugs

Standing Shoulder Shrugs

This exercise opens the chest, strengthens the muscles between the shoulder blades and balances the big trapezius muscle on your back.

First, stand with your feet hip-width apart and facing straight ahead. If possible, have your heels touch the wall. If this makes you feel like you are going to fall forward, move your feet out slightly. Let the wall support you and align your load bearing joints—ankles, knees, hips, and shoulders. Your head may or may not be on the wall, depending on your upper back position. Keep your chin parallel to the floor.

Next, pull your shoulder blades down and together toward the spine. The movement should come from your upper back, not your arms. Keep your arms relaxed at your sides with your thumbs facing forward. You should feel more contact on the wall with your scapula (shoulder blade) bone as you engage these muscles.

NOTE: Maintain a neutral rib cage position when pulling the blades together and throughout the exercise. Your sternum in the center of your rib cage should remain parallel with the floor. There is a tendency for the chest to lift and lower back to overarch.

Now, keeping your shoulder blades pulled back and in contact with the wall, shrug your shoulders up. We all tend to be good at this. Ha! While doing this, you should hear your scapula sliding up the wall.

Next, and more importantly, press your shoulder blades down toward your feet while still keeping the contraction in your back, blades on the wall and spine in neutral. You may feel engagement of muscles below your shoulder blades and also a stretch in your neck and chest.

Hold this position with your shoulder blades pulled down for at least two seconds before shrugging them up again.

While you shrug up, inhale through your nose. Then, exhale out your mouth as you press down and hold. Repeat several times.

Flexion Abdominals Arm Glides

This exercise works on the rotational movement of the shoulder blades while stabilizing the pelvis. As Egoscue notes in Pain Free, “The shoulder is designed to both hinge and rotate. When its rotational capability is restricted, the elbow is recruited to handle the assignment.”

First, lie on your back with feet pointed straight up on the wall. Your lower leg is parallel to the floor. Scoot your butt in close enough to the wall so that you are in deep hip flexion, with a greater than 90-degree bend at your hips, ~6”. While in this position, place a 4-6” block or ball between your knees and squeeze lightly. This should cause you to feel the work in your inner thighs and also in the front and center of your hips where they are bent. Maintain this position throughout the exercise.

inner thighs and also in the front and center of your hips where they are bent. Maintain this position throughout the exercise.

Now, place your arms in a 90-degree position with your elbow and shoulder directly in line with each other and wrist to elbow parallel to the side of your body. Maintain this 90-degree bend in your elbow as you move your arms; do not straighten them.

While keeping the back of your arms, wrists and hands on the floor as best you can, slide your hands together over your head until your fingers touch. Then slowly lower back down to the starting position.

While keeping the back of your arms, wrists and hands on the floor as best you can, slide your hands together over your head until your fingers touch. Then slowly lower back down to the starting position.

So that you hold your core in a neutral position, without arching the back and lifting the chest, exhale out your mouth as you raise your arms, which engages your abs gently, and inhale through the nose as you bring the arms down. Repeat several times.

Kneeling Arm Circles

This exercise strengthens your upper back and shoulder muscles. If kneeling is uncomfortable, you can do this sitting or standing.

First, kneel with your knees hip width apart and feet turned under with the tops of your feet on the floor. While in this position, use the golfers grip: keeping the palm open, curl your fingers in and extend your thumb. This grip activates the forearm muscles to lock out the wrist joint. Additionally, you should keep your elbow joint locked while doing this exercise to promote work in your shoulders.

First, kneel with your knees hip width apart and feet turned under with the tops of your feet on the floor. While in this position, use the golfers grip: keeping the palm open, curl your fingers in and extend your thumb. This grip activates the forearm muscles to lock out the wrist joint. Additionally, you should keep your elbow joint locked while doing this exercise to promote work in your shoulders.

Next, reach your arms out. This will cause you to feel a stretch across the front and back of your shoulders. Then, pinch the shoulder blades down and together (like in the standing shoulder shrugs). Pinching the shoulder blades helps to stabilize the upper back and shoulder. If you are feeling a lot of work in the top of your shoulder near your neck, pinch your shoulder blades down and together more.

Next, reach your arms out. This will cause you to feel a stretch across the front and back of your shoulders. Then, pinch the shoulder blades down and together (like in the standing shoulder shrugs). Pinching the shoulder blades helps to stabilize the upper back and shoulder. If you are feeling a lot of work in the top of your shoulder near your neck, pinch your shoulder blades down and together more.

Now, with your thumbs pointing forward, circle your arms forward, working up to at least 20 circles. The circle should be the size of a dinner plate going in front and behind the body. If you feel your pelvis rocking, don’t worry: this is a natural response to this movement and is activating the stabilizing muscles around the hip joint.

Finally, turn your hands palm up with your thumbs pointing back, and then circle backwards.

As you become stronger, don’t drop your arms between the forward and backward circles. Then, increase your reps.

Summary

Clearly, elbow tendonitis is often not a problem within the elbow. Instead, the elbow is trying to be the shoulder. Because the elbow is not designed to do the work of the shoulder, it gets overtasked and causes pain. If you address the cause of the injury—the lack of shoulder mobility and function—you can then fix elbow tendonitis. As you can see, the shoulder, by its design, should be the most mobile joint in the body!

In order to realign your body and alleviate elbow pain, try the exercises provided. Although they may be challenging at first, you will improve with practice. Afterward, or at any time, let’s connect! Contact me if you have questions or would like to set-up a free, no obligation consultation.